The discovery of a Clap-net

Malcolm Simpson

It was at the AES Annual exhibition of 1980 that I first met Michael Chalmers- Hunt, when he encouraged me to make a collection of entomological bygones and started my collection with a gift of an old Victorian glass chloroform bottle and several entomological dealers' old catalogues.

Michael had built up an impressive collection of entomological memorabilia, which is now held at the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. There was, however, one item that he had failed to locate: the clap-net. In discussions I had with Michael I recall his great disappointment at not having found a genuine clap-net despite searching the length and breadth of England.

In May 1978 the Entomologist's Record published an article by Dr. R. S. Wilkinson entitled The History of the Entomological Clap-Net in Great Britain, in which he stated: ... not a single genuine clap-net has ever been discovered by the author or Mr. J. M. Chalmers-Hunt, and both of us have been searching for one for many years.

In Archives of Natural History (1994) 21(3) Michael Chalmers-Hunt recorded that "Having searched assiduously but unsuccessfully for many years for a genuine clap-net, I had come to the conclusion that no such article survived." I too had searched unsuccessfully for over 26 years and, like Michael Chalmers- Hunt and many others interested in the history of entomological collecting equipment, shared the view that: no such article survived

.

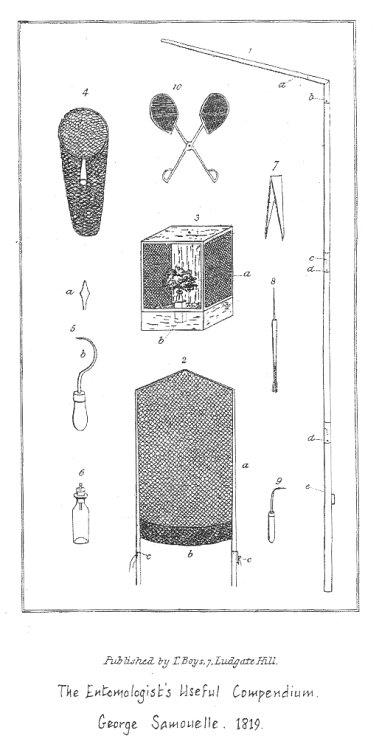

It is not always that one's labours are rewarded, so it is particularly pleasing to record that my 26 years of searching has finally come to fruition. In late January 2007 while assisting Darren J. Mann (Collections Manager of the Hope Entomological Collections, Oxford University Museum of Natural History) to prepare some old entomological equipment for public display at the museum, we came upon a number of old butterfly net parts. These parts once made up four separate net frames but so many parts were missing it was possible to reconstruct one complete kite net frame only. Anxious not to discard the remaining parts I obtained permission from Darren to take the items home for more leisurely consideration. I was certain that some of the unusual parts were from old butterfly nets but they just did not conform to the scope of my experience up to that time. However, during my researches I checked through many references to the clap-net in old literature including those in George Samouelle's Entomologist's Useful Compendium of 1819. Samouelle not only gives a detailed description for making a clap-net but helpfully gives a clear illustration (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 - George Samouelle's illustration of a clap-net

It was only when looking at this illustration that I realized the net parts I had long puzzled over made up one complete clap-net rod and one third of a second rod. Samouelle played no small part in this momentous discovery. His recommendation for constructing a clap-net is:

"The net rods should be made of ash, beech, hazel, or any tough wood; each rod should be about five feet in length, perfectly round, smooth and gradually tapering... the rod must be divided into three or four pieces for the convenience of being carried in the pocket... when fitted together, care must be taken in fitting the joints to the brass tubes, that they are made exact or otherwise they will be subject to shake and continually coming to pieces."

While being similar in appearance to Samouelle's clap-net, the Hope version has each rod made up of six parts (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 - An illustration from George Samouelle's Entomologist's Useful Compendium showing the structure of a clap-net

The wood is hardwood, round and tapering and the brass joints exactly fit the wooden rods. The brass joints of the Hope clap-net are threaded and because they reduce in size along the length of the tapered rod, each thread is different and therefore not interchangeable. The rods fulfil Samouelle's specification although he recommends that they should be about five feet in length

whereas the Hope clap-net is only four-feet, five-inches long. The rods taper from 5/8" at the handle to 3/8" at the termination of the cross piece. The angle of the cross piece to the rod is 120 degrees which nearly corresponds to Samouelle's diagram.

The Hope clap-net is of a high standard of construction, being professionally made, and was probably suppled by one of the larger London entomological equipment dealers, many of which were trading at the time clap-nets were in use. Moses Harris, in The Aurelian of 1766, directed collectors to purchase them: at the Fishing-Tackle Shops, by asking for them; they call them Butterfly Traps.

So how long was the clap-net in use? We know that in 1742 Benjamin Wilkes published directions for collectors which contained probably the first ever description of the clap-net, Provide a Net made of Muscheto Gause, and in shape like a Bat-fowling Net.

The most recent record I a have of a clap-net in use is from personal correspondence with Raymond Cave of Ludlow who remembers a battered example of a clap-net being used by William Foddy of Rugby in 1938. The great entomologist Petiver returned from a visit to the Netherlands in 1711 urging collectors to use the net employed by continental collectors, namely the bag or ring net, but he made no mention of the clap-net and there is no record of what type of net, if any, was being used in Britain at that time. We do know that Moffet, in his Insectorum sive minimorum animalium theatrum of 1634, recounts using a branch of the broom-plant, which he was using to capture insects, in order to defend himself from attacking wasps. So we have to assume that the clap-net came into use for collecting insects some time between 1634 (Moffet) and 1742 (Wilkes) and was still in use in 1938 (Cave), a period of well over 200 years. Considering the number of clap-nets that would have been used over such a long time it is most surprising that until now no surviving clap-net has been found. One explanation could be that, as no examples were available for examination, the form of the clap-net was not readily recognisable. Although the Hope clap-net is almost complete, it was fully two days before I realised that at long last the object in front of me was a genuine clap-net!

Although there is no provenance for the Hope clap-net there is no doubt that this is a most important historical discovery in entomological terms, especially as it was discovered in such an eminent establishment as the Hope collections. Its discovery fills a significant gap in the range of surviving collecting equipment used in Britain over the past two hundred years and will no doubt be a celebrated exhibit in the Hope Collections, Oxford, for anyone with an interest in the history of butterfly collecting in Britain.

The AES played no small part in this important discovery as it was through my membership of the Society that I met both Michael Chalmers-Hunt and Darren J. Mann.

References

Hams, Moses (1766), The Aurelian.

Moffet, Thomas (1634), lnsectorum Sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum.

Samouelle, George (1819), The Entomologist's Useful Compendium.

Originally published in the Volume 66 of the Bulletin of the Amateur Entomologists' Society.Back to articles list.

![Amateur Entomologists' Society home page [Logo]](/images/aes-logo-wplant.gif)