Breeding Marumba quercus, the Oak hawk-moth (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae)

Benoit Méry

I bred this species during the summer of 1989 and would like to clear up a few points regarding the requirements of this species.

Plate 1 - Adult Oak-hawkmoth

Eggs

I kept the eggs in a cardboard box. I never sprayed them with water. I just placed a branch of oak in the box to ensure there was a slight degree of humidity. However, on the whole they were kept dry.

Larvae

Plate 2 - Larva of the Oak-hawkmoth

The larvae hatched satisfactorily. First instar larvae do not feed. They settle down on the rib of a leaf, spin a silken support and prepare to moult. The first moult takes place two to three days after hatching.

The larvae were reared through all their stages on Quercus pubescens(downy oak).

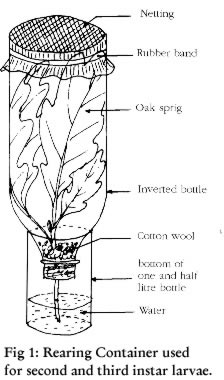

When in their second and third instars, the larvae were reared in inverted 1.5 litre plastic bottles with the bottom removed (Figure 1), and replaced by netting with a 1mm mesh; this prevented any condensation inside the bottles. Ten larvae were reared in each bottle.

Lighting

The bottles were placed behind a window provided with curtains with a very fine mesh, providing maximum protection from high temperatures, as a result of sunlight.

Temperature

Minimum 25°C by night. Maximum 30°C by day.

Humidity

This was provided by the foliage; I never sprayed with water.

Foodplant

During the initial stages I was away during the week. Unfortunately there was a week when the weather was exceptionally hot, and the foodplant dried out in the bottles. I lost two-thirds of my larvae, as they were without any fresh food for one or two days.

The only larvae which survived were those which were moulting (second and third instars). There were six in all. Oddly enough, the two larvae most severely affected by the lack of food lost their horns during the following instars.

Later on, I reared the larvae in a large wooden cage (40 x 40 x 60 cm) with net sides, so as to ensure ample ventilation and allow light to enter. This cage was placed behind a window, exposed to direct sunlight throughout the afternoon. To prevent overheating (above 35°C) the window was left half-open during the day, to provide ample ventilation inside the cage. The foodplant was replaced every other day. I noticed that the larvae grew more slowly as soon as they started feeding on oak which had been cut more than two days before.

The larvae will only move to a fresh leaf when they have eaten the old one. Unless the foliage is withered and dry, the larvae always remain on the same branch, towards the tip; they are very lethargic.

This presents two problems for the breeder:

The larvae must be transferred onto fresh food; if this is not done, they would remain on the old branch, where they would die.

If two larvae were to meet on the same leaf, each of them would prevent the other from feeding; neither would give way to the other. For this reason the breeder must avoid placing several larvae on the same branch. This is why I believe breeders always state that larvae should be bred in isolation!

During the latter stages, the larvae were reared under conditions similar to those which they would have encountered in the wild in southern France:

- Temperature ranging between 25°C by night and 35°C by day.

- Very low humidity (the larvae were never sprayed with water).

- The cage was ventilated throughout the day (the larvae seemed to eat more easily when the cage was ventilated).

- The cage was placed in direct sunlight for half the day.

Pupation

The larvae pupated in earth at a depth of about 5cm.

Hibernation

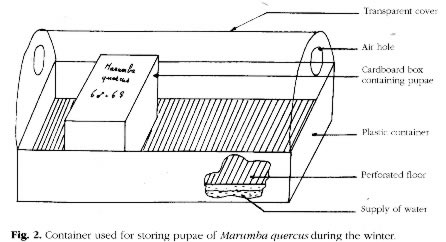

The pupae are very susceptible to attack by mildew as soon as they are removed from their pupal cell and placed on a damp support (Figure 2).

There must be no direct contact whatsoever between the pupa and the moisture itself; this is absolutely essential.

For my part I have made a cage where the pupae can spend the winter, and this has given me complete satisfaction. This is a mini greenhouse used for plant propagation. The bottom of this propagator is filled with water. The pupae are stored in cardboard ' boxes, and these in turn are placed on the plastic plate covering the water supply.

Breeding: Discussion

- Breeding seems to have been fairly successful; although food was lacking during the second instar.

- In the first place, breeding is not so difficult as it would appear. Constant care is the only requirement.

- I see no grounds why the eggs should not be kept dry (but not placed in bright sunshine!).

- The larvae can stand prolonged exposure to sunlight, provided leaf shade temperature does not exceed 35°C. The cage simply needs airing and ventilation to prevent overheating. If a badly-ventilated cage is placed in the sun, the consequences can be fatal as far as the larvae are concerned; the effect would be the same as if the larvae were inside an oven.

- It is not absolutely necessary to rear the larvae in isolation. They just need enough room to make sure they do not meet each other.

- Finally, the larval foodplant must be fresh; this is by far the most important factor.

- Above all, be patient! Breeding takes more than six weeks under the above conditions.

Back to articles list.

![Amateur Entomologists' Society home page [Logo]](/images/aes-logo-wplant.gif)